About the D&RGW 223

History of the D&RGW #233 by Joshua Bernhard, member of the Golden Spike Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society.

The years during and immediately following the Civil War were a period of development for American railroads. As the Pacific Railway Act opened up new opportunities for railroad construction in the west, in the East heavy industry was rapidly growing which resulted in high demand for coal, as steam was replacing water as the most reliable energy source. At the same time, those years saw the merger of hundreds of fragmented rail lines into what would later become the giants of eastern railroading.

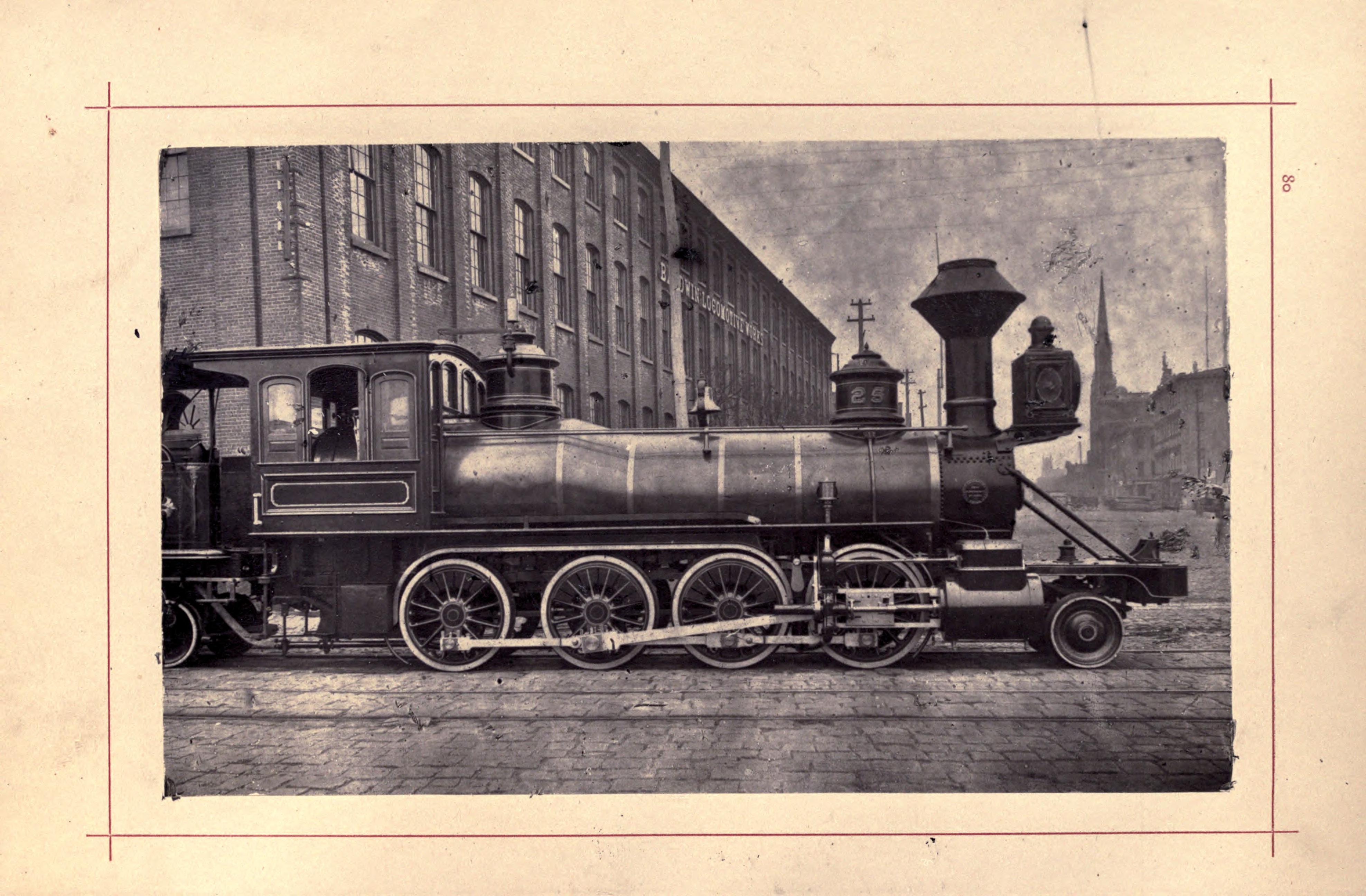

One of the most aggressive lines was the Lehigh Valley, which with the success of its own business, began buying out competitors as early as 1864. In 1866, the Lehigh Valley absorbed both the Lehigh and Mahoney Railroad and the 105-mile North Branch Canal, one of its largest acquisitions, which coincided with the design of a new type of locomotive designed by Alexander Mitchell. The LV approached several manufacturers with the plans, and Baldwin produced the locomotive in July of that year. While this was not the first locomotive with four sets of drivers, it was the first time a pony truck had been placed on the front end, and it served well. The Lehigh Valley named the locomotive “Consolidation” in honor of its acquisitions, which in time came to be the universal designation for all locomotives of the 2-8-0 type. By 1872 Baldwin proudly announced in their catalogs that “over thirty…have since been constructed.”[1]

Baldwin Consolidated Steam Locomotive from the Baldwin Illustrated Catalog, 1872.

The year before, in 1871, the newly formed Denver & Rio Grande Railway ordered its first locomotives, tiny 2-4-0 and 2-6-0s, from Baldwin for its planned Colorado empire. The D&RG, inspired by the narrow gauge Ffestinog Railway in Wales, was building a three-foot gauge line from Denver south to Santa Fe. While not the first narrow gauge locomotives built, they sparked what would later be called the Narrow Gauge Frenzy as dozens of 3-foot-gauge railroads were formed throughout the Rocky Mountains and Great Basin during those latter decades of the 19th century.

Perhaps anticipating the D&RG’s future need for greater power, Baldwin scaled down their design to produce the first three-foot gauge consolidation in 1873. Baldwin had to wait for results, though – it wasn’t until 1877 that the Rio Grande would consider such a locomotive profitable. In 1876 the road had started pushing west from Cuchara, Colorado, up over La Veta Pass to the San Luis Valley, where it was hoped that a profitable agricultural trade could be found. The pass, at an altitude of 9,400 feet, was the highest railroad in the country and needed stronger power. While the problem of pulling power could theoretically be solved with increasingly larger 2-6-0s, one major obstacle was that the lightweight rail used on the D&RG would not support heavier locomotives without a more even distribution of weight. By adding one more powered axle, greater strength could be achieved without having to upgrade existing track.

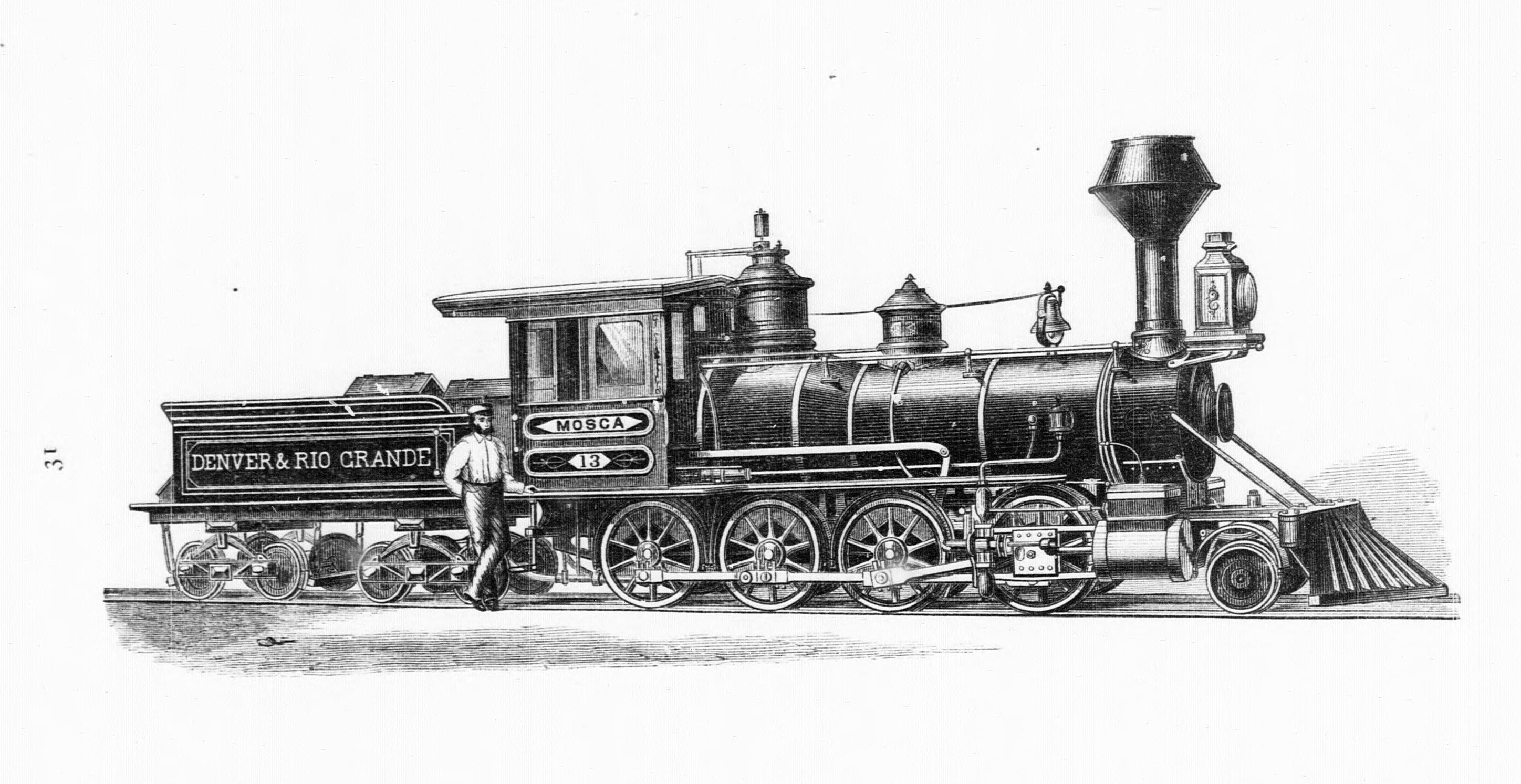

D&RGW Mosca Narrow Gauge Engine

The first of what would later become the C-16 class, indeed the first consolidation on the D&RG system, was at that time the largest locomotive on the railroad, whose roster was dominated by tiny 2-6-0 and 4-4-0 Moguls and Americans. It was given the number 22, following the early pattern of numbering locomotives chronologically as acquired, and named the Alamosa. The 22 initially replaced the oddball British-built 0-4-4-0 articulated Fairlie locomotive number 101 on coal trains between Divide and South Pueblo, and was very successful[2].

During test runs, the Rio Grande superintendent telegraphed Baldwin to report that the “…engine ‘Alamosa’ had just hauled from Garland to the Summit [of La Veta Pass] one baggage car and seven coaches, containing one hundred and sixty passengers…the engine worked splendidly, and moved up the two hundred and eleven feet grades and around the thirty degree curves seemingly with as much ease as our passenger engines on seventy-five feet grades with three coaches and baggage cars.”[3] This locomotive was classified as a type 60N, a rather crude designation based on unloaded weight and track gauge, meaning that number 22 was narrow gauge (N) with an unloaded weight of close to 60,000 pounds. This classification system resulted in some confusion, as locomotives of any type could be classified together regardless of use or physical characteristics, based solely on their weight. As an example, in 1883 the D&RG received seven class 40N locomotives from the Denver & Rio Grande Western in Utah, although these were an eclectic mix of 4-4-0s, 0-6-0s, and 2-6-0s.

Number 23 was the second Consolidation, although of a smaller size (56N), and was received later that same year. Over the following years all further 2-8-0s were of this class until 1880 when it was realized that the 56Ns were underpowered for the mountain grades, and two more class 60Ns were received, numbered 41 and 42. The only physical difference between these early 56N and 60N classes were the larger boilers on the latter.

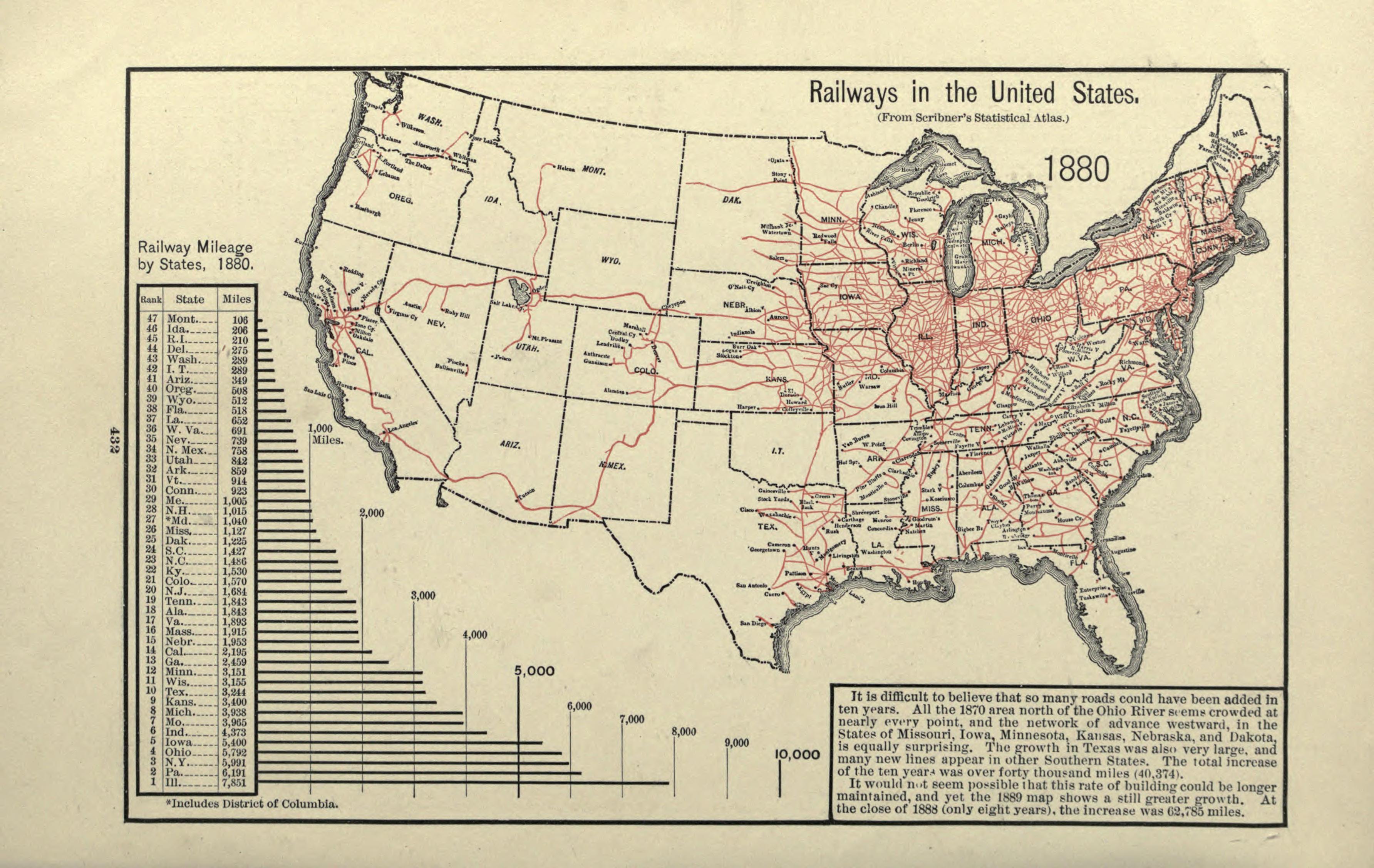

1880 Map of American Railways, Construction & Development

The year 1881 marked the high point in the history of the Denver & Rio Grande. As stated by historian Robert LeMassena, “This was the D&RG’s year of glory.”[4] The road was rapidly expanding, Colorado was growing as the Rocky Mountain mines churned out ton after ton of precious ores, and expansion towards the Mormon capitol in Utah was rapidly underway. It is of no wonder that a small footnote in the December edition of simply stated “The Rio Grande received twenty new narrow-gauge locomotives of the Consolidation type, this week.” New locomotives were a common occurrence during those exciting times, so there was little need to elaborate. Yet these new locomotives would turn out to be important. They were a gathering of the new 60Ns, consolidations, some of the biggest narrow gauge locomotives in the world at the time.

Among these winter arrivals was the 223, which at a cost of $11,553 was the most expensive locomotive purchased by the Rio Grande to that date. The 223 was an unassuming locomotive, missing the chance to receive a name by only four places (the Rio Grande named the first 19 of the Grant locomotives, but for some unrecorded reason stopped with number 218). These newer 60Ns differed from the older 60Ns and 56Ns in that the frame was welded instead of bolted, a fairly new practice in locomotive construction.

Up to this point the D&RG had relied exclusively on Baldwin for its motive power. However, with this huge order, a strange twist of fate resulted in the first 28 of the new 60Ns being constructed by Grant Locomotive Works. Apart from the single solitary Fairlie, these were the only non-Baldwin narrow gauge products on the D&RG system until the purchase of the 140N (K-27) class from ALCo many years later in 1923. Baldwin had received more orders than it was able to handle (including the largest single order ever received of 150 locomotives for the Mexican National Construction Company), and thus passed on parts of their contracts to other locomotive builders, but no record exists to suggest why Grant, of all the locomotive manufacturers in the U.S., was chosen[5]. As a general rule, these Grant products were similar to the Baldwin plans, with the exception of the frames and some Grant castings such as the domes, and accounted for more than half of that year’s production of consolidations, a fact that R. Suydam Grant, president of the company, felt worthy to note in the official history of his company.[6]

Grant completed the first 23 locomotives that same year. These were given numbers 200-221, and then unexplainably skipped to 223, which was received by the railroad in December. Numbers 222 and 224-227 were delivered the following year. Baldwin constructed numbers 240-255, delivered in 1881, and numbers 256-291 and 294-295, delivered in 1882, concluding the 60N series. The Baldwin locomotives showed some changes to the original 60N plans, most notably a longer smokebox. Observant readers may notice that 292 and 293 were excluded from the list – although built, these two locomotives were never delivered to their intended owner. Later, in 1894, the railroad would include numbers 22 and 41 in the new numbering system as numbers 228 and 229 respectively. With the 1882 deliveries of the new locomotives the D&RG roster reached a total of 172 freight locomotives.

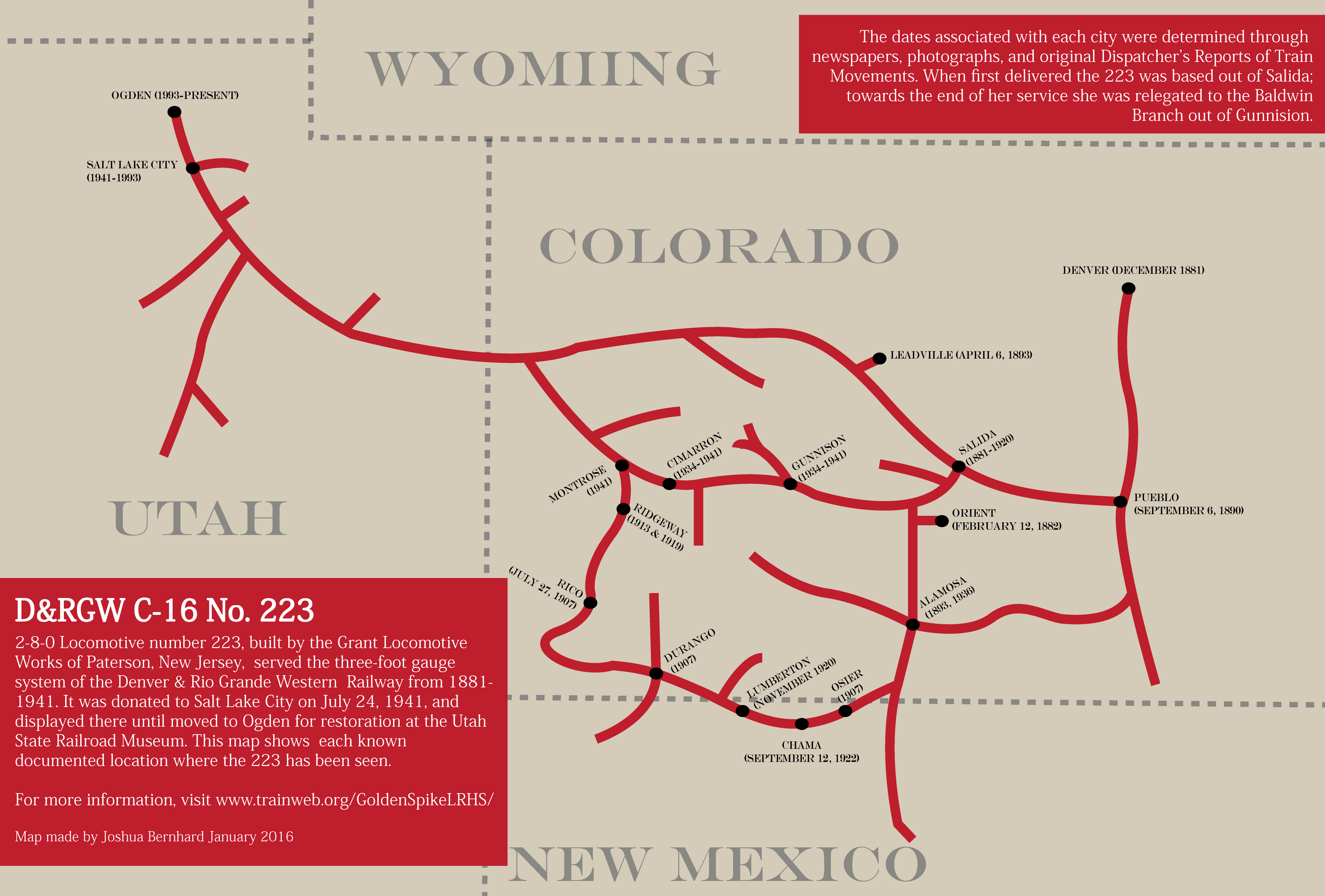

Salida, being a division point on the railroad, was the assigned terminal for many of the new consolidations, including the 223. The railroad constructed large repair shops there, and its position on the line made it “one of the most important stations on the entire system.”[7] It was there that the first known record of the 223’s operation was made, on February 12, 1882, as westbound mixed train number 87 to Orient. From Salida the 223 pulled trains to nearly every line and branch on the Colorado system, all the way to Leadville, the Mile-high City,[8] although there is little recorded of those first few years of service.

Over time the D&RG sold off the 60Ns. Eleven, all of them Baldwins, were turned over to the Denver & Rio Grande Western when that company split from its parent D&RG to operate the Utah Extension (these are the only locomotives of the future C-16 class that have record of service in Utah). In 1890 three more Baldwins were sold to the Rio Grande Southern, and the following year sixteen more were sold to the same company. The Rio Grande appeared to have a preference for the Grant locomotives, as none were sold during this time. The 1895 Official Roster shows 53 60Ns in service, a drop of 31 since 1882, and not a single Grant was missing.

As time went on, each locomotive slowly adopted its own distinct appearance as the 60N class evolved through upgrades, accidents and rebuilds. Perhaps in an effort to standardize, the D&RG purchased new rounded dome castings from Baldwin and began to replace the old Grant castings. This was an unorganized effort, however, and many photographs demonstrate locomotives with two different styles of domes, fluted and rounded, and even then the fluted domes varied from engine to engine. Rather than produce new drawings to duplicate the original Grant frames, D&RG crews simply replaced them with Baldwin-style frames between 1908 and 1909. New federal laws also required the installation of US safety appliances to all locomotives in 1912. Tenders were mixed and matched as older locomotives were scrapped. By the end, it was difficult to determine that any of the 60Ns were related.

Throughout all this, the D&RG passed through several reorganizations and receiverships, which did little to affect the locomotive fleet until December 1923. As the D&RG prepared to reorganize into the second Denver & Rio Grande Western company, the entire locomotive fleet was reclassified according to wheel arrangement and tractive effort. Accordingly the 60Ns became C-16s – Consolidations with a tractive effort of approximately 16,000 pounds (this figure varied from locomotive to locomotive). By this time the narrow gauge consolidations were aging – the majority holding 42 years of service, which is admirable in a steam locomotive[9] – and the C-16s rapidly slunk to the dead lines and second-hand dealers as the years went on. The first big wave of scrapping occurred in 1926, when 29 of the C-16s remaining on the Rio Grande system were simultaneously sent to pasture.

The 223 was involved in a deadly wreck at 4:50 a.m. on September 6, 1890, near Adobe, Colorado, where the standard gauge track of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe paralleled the Rio Grande. Train number 61 was split in two sections, with 223 and sister C-16 240 leading the first section, following train number 40. Somehow train 40 stalled, so the first section of 61, a mixed train with two coaches of sleeping laborers stopped also. Unfortunately, the second section, headed by engine 560, was following either too closely or too quickly, and rounding the sharp curve collided with the rear end of the first section. Two coaches and the caboose of the first section were telescoped, killing five Italians and wounding around 35 others[10]. The early morning nature of the accident no doubt contributed to the visibility issues.

The wounded were taken as quickly as possible to Florence for treatment, doctors were called from Pueblo, Florence and Cañon City, and the Italian Consul was notified of the dead and wounded immigrants. Amazingly, the crew of the 560 was unharmed. In total, two coaches, the caboose, the 560, and twelve freight cars were scattered across both the D&RG and AT&SF tracks. The 223 being at the head end escaped scott free, although this would not be her first disaster.

December 11, 1892, was a Sabbath, but for the Denver & Rio Grande employees in Salida it was anything but holy. Early in the morning at 5:45 a fire was noticed in roundhouse and the alarm was spread, waking the entire city with the shrill blast of the shop whistle. The roundhouse and shop in Salida were always full, and on this day many of the stalls were double stacked with locomotives outside the building on the turntable leads, which thwarted the crews in their attempts to pull the locomotives that were inside the roundhouse to safety. In addition, the city’s water lines were frozen, the fire company’s hose was leaky, and the oil-soaked floor and combustible nature of locomotive fuel caused the fire to spread rapidly. The shop was destroyed before the water was even turned on. As the fire raged on the men turned their attention from saving locomotives to saving the equipment in the dispatcher’s office, the company records and furniture being deemed much harder to replace than the engines, and they cut the telegraph wires further hindering communication: the news of the fire was communicated to surrounding communities by patrons of that morning’s passenger trains. Around noon the Salida and railroad fire companies together had the fire under control; the stone wall of the old portion of the roundhouse kept the flames at bay on that side, saving the locomotives and machinery kept there.

The fire, which was determined to have started in the cab of C-19 number 419, finally consumed four standard gauge locomotives and 13 narrow gauge locomotives, including the 223, which was trapped in its stall. Luckily for the railroad the damages were covered by insurance and all the narrow gauge engines, called “chippy” by the newspapers,[11] were sent to Alamosa to be rebuilt. The 223 was back in service by April 1893.

As fate would have it, the 223 would once again be burned in another early morning fire on January 17, 1905, this time in Gunnison. At four o’clock the fire was discovered; by the time it was under control, it had destroyed six stalls, the stationary boiler, and all machinery. Although there were twelve locomotives inside the roundhouse, rescue efforts were much more successful than those in Salida 13 years earlier. Initial reports claimed that the loss totaled nine locomotives and over $50,000; as time was given to investigate, the losses were dropped to $15,000 and just two locomotives, the 223 and 218. The 223 was carrying a wedge plow on her pilot for winter service at the time. Both locomotives were completely rebuilt, and the 223’s tender cistern was replaced.

The 223 and several other C-16s were again rebuilt between 1908 and 1909, having developed crystallized frames. The Rio Grande replaced most of the Grant-style frames with home-built frames to the Baldwin design; this change was applied to the 223. She was rebuilt yet again as World War I swept across Europe, receiving a new tender frame and steel boiler in 1914.

During these first two decades of the 20th century the 223 slipped back and forth between the D&RG and the Rio Grande Southern. In 1907 the 223 and sister Grant 203 were operating between Rico and Durango on the RGS; the 223 was loaned again for short periods in September 1913 and August 1919. In July 1915 she was upgraded with a new electric headlight, installed in the old box headlight casing at a cost of $176.41. In November 1920 the 223 was loaned to the New Mexico Lumber Company for ten days, which seems to have been part of a pattern of C-16 swaps as number 204 was loaned to the same company for the first 20 days of that month, and in December the 223 was replaced with number 201 for a period of two weeks.[12] On September 12, 1922, the 223 was in Chama, New Mexico, where it collided with the 222 in the yards. No official record of damages was kept, although the 223’s engineer was given ten demerits. It is possible that during the early 1920s the 223 was stationed out of Chama as photographs show it in service at Osier near the halfway point of that city and Antonito, Colorado. Chama was the access point to the New Mexico Lumber Company, which interchanged with the D&RGW at Lumberton approximately 25 miles to the west.

The 223 was eventually permanently stationed at Gunnison, a junction town described in Rio Grande tourism literature as “[An] enterprising place…in the heart of gold, silver, lead, copper and coal country.”[13] The 223, alongside number 278 was used on the Pitkin, Lake City and Baldwin branches. The Lake City branch was sold in 1933, and in 1934 the Rio Grande considered abandoning the Baldwin Branch until new coal deposits in Baldwin and Kubler caused an increase in traffic and saved it from the scrappers.

The sixteen-mile Baldwin Branch was constructed by the Denver, South Park & Pacific in 1882 using 35-pound rail and stub switches. It became the Ohio Creek Branch of the Colorado & Southern when that company absorbed the DSP&P in 1899, and in 1911 the D&RG traded its Blue River branch for operating rights of the Baldwin branch (the C&S retained ownership), and throughout these years the track and bridges were never upgraded, resulting in strict weight restrictions. The remaining C-16s were the only locomotives small enough to operate the branch, which perhaps extended the 223’s life a bit longer as there was a legitimate need for the aging locomotive. The branch served several coal mines, although cattle and sheep were also major commodities each spring and fall.

The 223 and 278 were inseparable siblings in Gunnison. Both locomotives accompanied nearly every train on the Baldwin Branch, each one splitting the switching duties at the different sidings; occasionally one would drop off at Castleton to switch the three-mile Kubler branch while the other continued to Baldwin to handle the Alpine Mine. Further complicating the operations, as the train progressed towards Baldwin, its maximum permitted tonnage decreased, which meant that any loaded trains exceeding 140 tons in Baldwin had to be taken to Castleton in several sections to be remade at the small yard there for the trip to Gunnison. Double-heading was prohibited, again due to weight restrictions, so the 223 generally took the lead and the 278 pushed from the rear of the train behind the caboose (a practice later banned due to the fragile nature of the wood caboose frames).

223 At the Gunnison Roundhouse, Colorado – Nathan Holmes Collection. Date and photographer unknown.

Interestingly, engine crews seemed to prefer the 223 over the 278, as every record of a single-engine train reports the 223 at the head end, whether it be work extras, stock trains, or an occasional emergency helper duty to Montrose (as was the case on December 11, 1936, acting as helper for extra 344 west, Gunnison to Montrose, and on the 12th, as helper to extra 344 east, Montrose to Gunnison). During winter months this may be because the 223 was equipped with both a pilot flanger and two air lines on the tender, one for brakes and the other to control the blade on a flanger car, whereas the 278 was not. The weight restrictions on the branch caused headaches in snow removal as well, since the rotary plows were too heavy, and the railroad could only rely on flangers, spreaders, and picks and shovels to remove snow.[14] During the winter months nearly every train to Baldwin was accompanied by flanger OJ or spreader OV, in addition to the 223’s pilot flanger hidden behind the cowcatcher.

During the Depression years the aging Baldwin Branch was plagued with problems, but so was the entire railroad. In 1935 the company declared bankruptcy and was placed into court-ordered receivership under Wilson McCarthy of Utah and Henry Swan of Colorado; for years maintenance on the entire system had been neglected. As the Baldwin Branch was still property of the Colorado & Southern, naturally its track suffered as well. A review of Dispatcher’s reports from the beginning of 1935 shows that derailments were almost as common as trains: Thursday, January 10, 1935: Castleton 1 hour 50 minutes picking ice and rerailing car. Tuesday, January 22, 1935: Baldwin 3 hours to rerail cars, off track on account of broken rail. Wednesday, April 24, 1935: La Plant four cars derailed, leaving four loaded cars and the caboose trapped. Tool car, ties and section crew needed to fix derailment. Thursday, April 25, 1935: Work extra with 223 and tool cars. 8 hours rerailing cars. Saturday, April 27, 1935: Work extra with 223 and four tool cars. 2 hours 50 minutes to rerail cars and 2 hours 10 minutes to repair track.

In the winter of 1936 the 223 was again slated for a rebuild, and to prepare for her absence the 268 was moved from Alamosa to Salida on November 12, then from Salida to Gunnison the following day. On November 17 the 223 Salida and was scrapped soon after. The 223 stayed in Salida twenty days and was returned to Gunnison on a three-locomotive train headed by the 499 with 493 and 495 as helpers, arriving in Gunnison at 9:55 that night. The 223 was accompanied by a “messenger”, of the last name Gill, who rode in the cab to ensure the safety of the locomotive. On December 15 the 223 and 278 were together again on the Baldwin branch.

Due in part to both William McCarthy’s program of line-pruning and reconstruction and the legal abandonment of the Colorado & Southern’s narrow gauge lines, the Baldwin Branch finally fell under complete Rio Grande ownership on August 13 1937. The Colorado & Southern left enough 70-pound rails and ties to completely rebuild the branch, which was done immediately, with the 223 and 278 heading the work trains daily, and drastically decreased the number of derailments due to track-related issues. Despite the upgrades the bridges were not rebuilt and the weight restrictions continued unchanged.

The other consolidations stationed out of Gunnison – C-19 344 and C-21s 360 and 361 – occasionally could not complete their duties, and the 223 was very often selected to replace one of the three in case of emergency. In January 1941 engine 360 was recorded as “out of service”, and the 223 accompanied locomotive 361 to Cimarron several times that month. It appears, however, that even the two locomotives together were underpowered at times – On January 16, the train was stuck in snow between Cimarron and Cerro Summit, so the crews dumped the cars and returned a few hours later with a flanger to clear the tracks. Two days later, on the 18th, the two consolidations made four unsuccessful trips from Cimarron to Cerro Summit, prompting the dispatcher to send K-27 461 light to Cimarron and the 223 returned to Gunnison. On the 25th the 360 was again in service and left Gunnison for Montrose with the 361, but the 361’s whistle failed just outside the city and the entire train returned to the yard. After an hour of preparation, the 223 took the place of the 361, but once again was replaced with a Mikado, this time number 454, near Cerro Summit. The 223 returned light to Gunnison.

On March 22, the Cimarron section foreman reported rockslides at milepost 325 near Curecanti; a work train was made up four loads and two empties led by the 360 and 223. Crews spent the afternoon from 12:30 to 4:05 clearing rocks, and forty minutes spreading cinders on the track. After a meal at Cimarron the train returned to Gunnison. The drill was repeated after a late snowstorm on April 2, the two locomotives pulling a very short train of one load and two empties; after clearing a snowslide at milepost 319 and setting out cars at Sapinero, the train returned to Gunnison with an even shorter consist of one empty.

Near the end of 1940, the city fathers of Salt Lake City wanted a steam locomotive to display in Liberty Park, and asked the D&RGW what could be done. Perhaps some searching was made through the roster to determine which locomotive was a likely candidate for an easy retirement, and for some reason lost to history they decided on the 223, perhaps because it was the most used of the last C-16s and was in need of a long-deserved rest. Regardless, the locomotive was taken from active service (the dispatcher’s reports show that she was operated regularly right to the end), sent to Salida once again and outfitted with a fake diamond stack and the shell of an ancient oil-burning headlight that was still lying around the premises. The pilot flanger and other useful parts were removed,including the knuckle couplers (links were placed in the coupler pockets in an effort to make look even older), the engine loaded onto standard-gauge flatcar 21203, and shipped to Salt Lake City in time for the July 24th, 1941, celebration of the day Brigham Young and his party of Mormon emigrants entered the Salt Lake Valley.

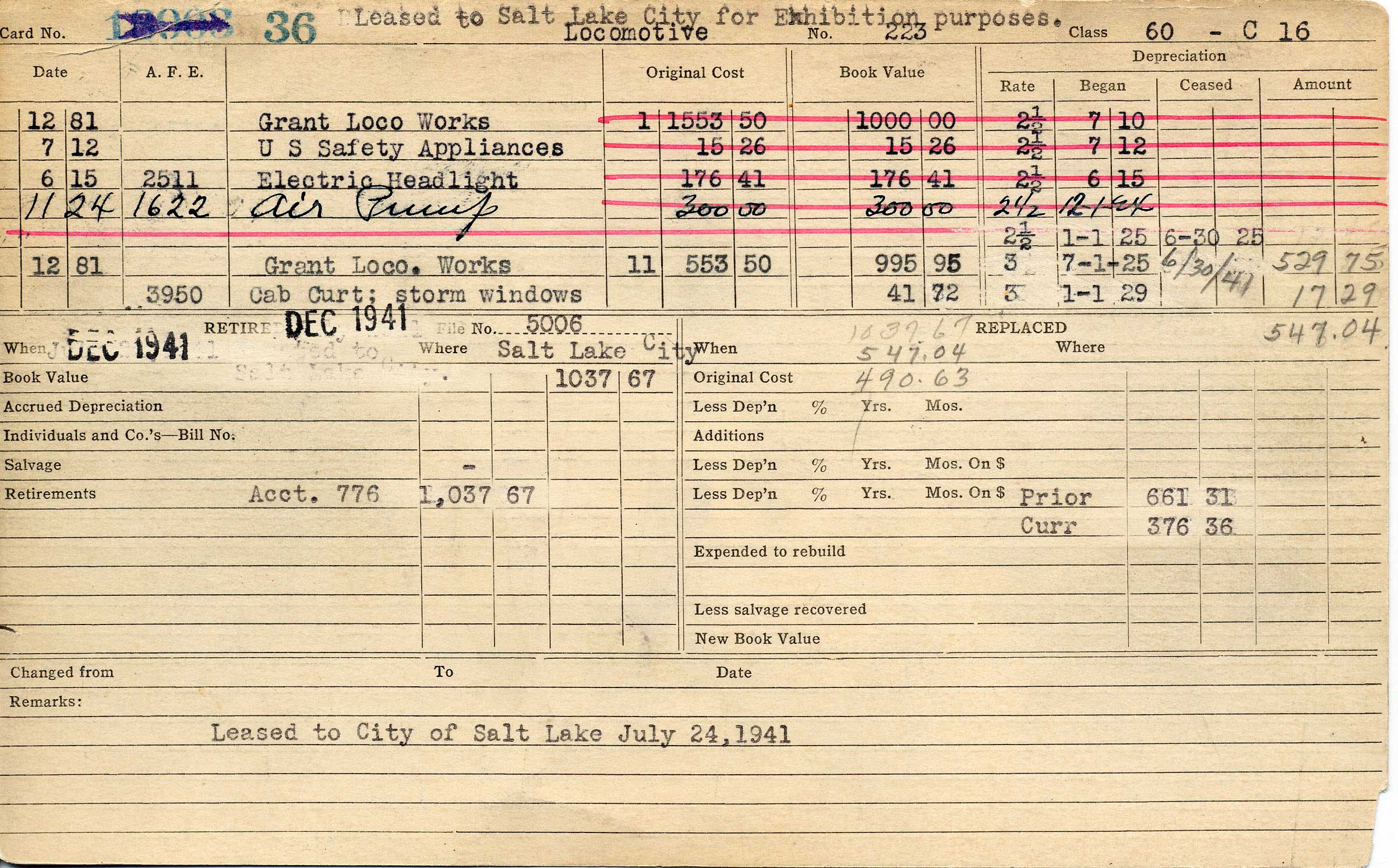

Paperwork showing the D&RGW 223 Leased to Salt Lake City with the costs for installing safety appliances, electric headlight, and air pump.

After parading through the city on a trailer, the 223 was placed on a short section of track near the Tracy Aviary in Liberty Park and formally dedicated. The band and choir from Richfield High School, a small mining town on the Rio Grande south of Salt Lake, provided appropriately patriotic musical accompaniment to the proceedings, which were directed by Dan Cunningham, master mechanic at the Salt Lake City shops, and included the reading of an executive order signed by Utah governor Herbert B. Maw on the 19th of that month:

“Whereas, the ninety-fourth anniversary of the arrival of the pioneers into Salt Lake Valley, being celebrated on July 24th, 1941, has appropriately been chosen for ceremonies incident to presentation by the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad of Narrow Gage Engine Number 223 to Salt Lake City. This engine, purchased by the railroad in December, 1881, and first used in Utah in 1883, will be placed in the Tracy Aviary at Liberty Park, and

“Whereas, I am mindful of the splendid contribution of Salt Lake City and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad to the progress and advancement of our commonwealth. This engine serves as a symbol of the close relationship that has existed between the city, state, and railroad for more than three-score years. “Now therefore, I, Herbert B. Maw, Governor of Utah, do hereby instruct that this communication be presented to the City of Salt Lake and to the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad. “In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused to be affixed the Great Seal of the State of Utah. “Done at the Capitol, Salt Lake City, this Nineteenth day of July, 1941.”

Strangely, none of the Rio Grande officials seemed to notice that the locomotive still had not been retired – according to the books the 223 was still available for service until December, and it would be another eleven years before the railroad vested itself of ownership. Even though the 268 permanently replaced the 223 on the Baldwin branch, later that year some may have regretted the decision of pulling the 223 from Gunnison – as the U.S. entered World War II, the Baldwin mines found a market in fueling the ships of the navy, and traffic on the Baldwin Branch picked up while the 223 idled in Salt Lake.

In 1952 R. Knox Bradford, vice-president of the D&RGW, hosted a second ceremony in which he legally gave ownership to the City of Salt Lake in the presence of city commissioner L.C.Romney. President Bradford presented a bronze plaque, which was affixed between the air compressors on the fireman’s side, giving a brief and inaccurate history of the 223’s operations (there is no record of the 223 ever entering Utah), and the Rio Grande’s Salt Lake shop crews donated time to cover up the garish and imaginative “1880s” paint with its as-retired 1930s lettering scheme.[15] Thus closed the final chapter in the 223’s seventy-one years of railroad service.

lthough many other historic vehicles were displayed in Liberty Park alongside the 223 over the years, including horse-drawn carriages and a World War II half track, the little locomotive was the most exciting feature of the park to the children who visited the Tracy Aviary. Gil Bennett, a railroad artist living in Utah, wrote “My father used to take the family to Liberty Park in Salt Lake City, to ride the merry-go-round and ferris wheel. I used to wander off to go see the big (to a four-year-old) steam locomotive.”[16] As the 223 influenced his love for steam, its thirty-year tenure in the park gave it a special connection to Utahns despite its lack of historical relevance to the state. However, it was generally neglected, and the park’s sprinklers watered the running gear as much as the grass. Finally the city deemed the locomotive useless for their purposes; they had plans to expand the children’s playground close by.

D&RGW 223 on display in Liberty Park in Salt Lake City, Utah. Photo from the Stan Jennings Collection. Used with permission from Joshua Bernhard.

In 1978, talks began of transferring ownership to the Utah State Historical Society, who nominated it for the National Register of Historic Places as #223 Grant Narrow Gauge Steam Locomotive, D&RG Class 60N, 2-8-0, a name which was eventually shortened to Grant Steam Locomotive No. 223 and was accompanied by an unfortunately poorly researched history. The Society was pushing to have the locomotive moved to the D&RGW/WP Union Station a few blocks to the northwest, which recently had fallen under the stewardship of the society and is now its headquarters. The 223 was formally gifted to the USHS on January 11, 1979.

The historical society removed the 223 from Liberty Park in 1980 with plans of cosmetic restoration. She was placed on the passenger platform of the Rio Grande depot, where it sat for several more years uncovered and neglected. “Restoration” consisted in removing loose metal and boxing it. The years of sprinkler soaking had taken its toll on the wood tender frame, which was visibly collapsing. Eventually a small shed was built around the locomotive, protecting it from further vandalism and deterioration, but hiding it from public view. The asbestos was also removed from the boiler, but the boiler sheathing was cut up and lost.

By 1989 the historical society seemed to lament taking on the locomotive. Money to restore it failed to materialize, and after more thoroughly researching the history written for the National Register the hard truth set in: as much as some might argue otherwise, the 223 “had no historical significance in Utah”[17]. The USHS put out the word that they had a locomotive for sale. The still-new Cumbres & Toltec Scenic Railroad in Colorado and New Mexico was quick to make an offer, as was the Colorado Railroad Museum in Golden. A Salt Lake City local, Cal Richardson, with high hopes of starting a Utah Museum of Science and Industry (it never happened) and strangely, the Utah Department of Transportation, were the only local parties interested in taking it on. Unfortunately, nobody stepped up to take on the locomotive. All plans for restoration were again put on hold, and even Mr. Richardson was pessimistic, saying “I could build it up to run. But I wouldn’t. It’s not worth it.” The 223 sat another three years, until the Union Station in Ogden was designated as the Utah State Railroad Museum by the state legislature. For several years the City of Ogden, which owned the building, had been collecting pieces of equipment from Union Pacific, as well as other display locomotives from around the state; with this official designation it seemed that it would be a feasible new home for the 223.

The Golden Spike Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive was organized in 1991 to support the new museum, preserve the state’s history, and perhaps most importantly, adopt the 223. The chapter dismantled the shed around the 223 and on September 26, 1992, successfully moved the 223 from Salt Lake to Ogden. The locomotive was placed behind the old Schupe-Williams candy factory just south of the Union Station; it was soon joined by three pieces of likewise narrow-gauge equipment that had been displayed at the Sons of Utah Pioneers Pioneer Village in Salt Lake, a short caboose, boxcar, and high-side gondola.

It was there that Maynard Morris got involved. A former nuclear engineer, he had experience in drafting, carpentry and machining, which would prove invaluable. He joined the group helping lay the short stretch of three-foot-gauge track behind the candy factory, and as time went on, he observed that “some of them were better talkers than doers, so I kind of migrated into taking the lead.”[18] Maynard spent weeks crawling over, under, and inside the tender, measuring every imaginable part and making meticulous CAD drawings. In need of a work space, the chapter commandeered an old Union Pacific 40-foot boxcar that was close by and installed lighting and electrical outlets. However, the majority of the work was done outdoors, which limited progress during winter. Bob Geier, director of the Union Station Foundation, recognized the rather Spartan circumstances of the restoration group and felt that the time was right to create a machine shop for the upkeep of the growing Utah State Railroad Museum collection; Richard Carroll, member of the R&LHS, presented the idea of using the then-vacant Trainmen’s building at the north end of the Union Station campus as such a facility. The city council and Union Station Foundation board agreed and installed temporary lighting and new windows; the R&LHS provided an alarm system. The tender was moved to the new building in late 1993, and Mr. Geier acquired large machinery, including lathes, drill presses, and bandsaws, through the Utah State Surplus Sales office (some of the tools date to World War II, and still work wonderfully). In 1996 Ogden City appropriated funds to upgrade the power supply for the use of industrial machinery and installed a new fire suppression system and space heating, making winter work just that much more comfortable. With a dedicated space to work, restoration on the 223 progressed slowly but steadily.

Sources: